Lesson #45,231 that My Husband has Taught Me that I Have Begrudgingly Accepted

RFK Jr Controversial Topic Series, Chapter 1: Autism

I am beyond frustrated by the CDC's recent announcement that they will further investigate vaccines and autism. My precious husband, bless him, must listen to my rantings on the regular about all the things currently happening in the public health arena and biomedical research. He deserves a medal.

However, he was kind of surprised that I was opposed to this idea of investigating vaccines and autism. He thought, "more research, my wife will love this." But his wife does not love this, and here is why…

We have decades of research that has been replicated over two dozen times and shows no link between vaccines and autism. Investing more money in studying this because the results don't align with the current HHS Secretary's beliefs is not a valid reason to waste taxpayers' money. I thought we were eliminating waste.

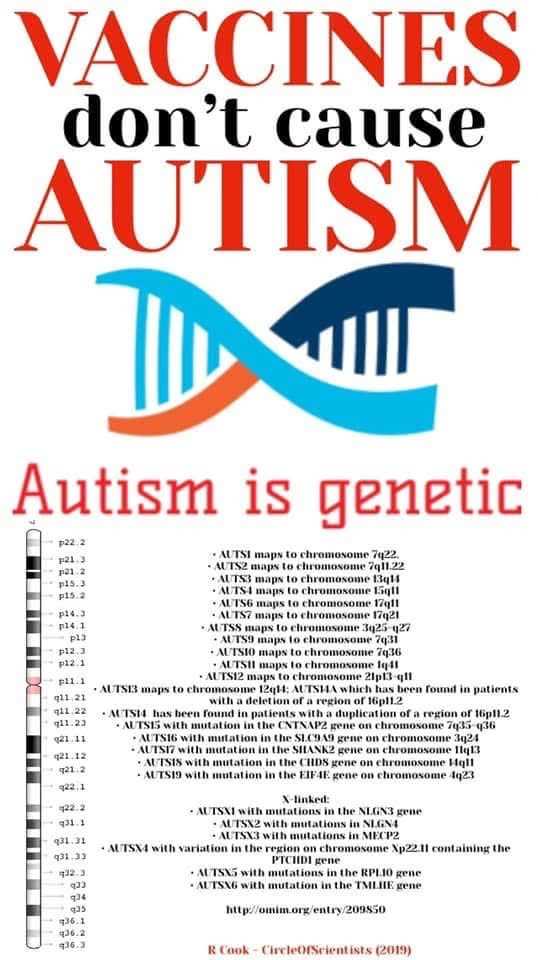

A better choice would be to invest in the research that has been making headway in our understanding of autism. This includes genetics research and research on other environmental factors, not vaccines. We now understand that autism is largely a genetic condition.

We have studies on heritability that indicate that genetics contribute to 40-80% of ASD risk.1

Twin studies show that monozygotic (identical) twins have a much higher concordance rate for ASD, estimated between 70-90%, while dizygotic (fraternal) twins only have a 30-40% concordance rate for ASD.1

We also have family studies that indicate ASD is more likely to develop in individuals with a family history of ASD.1

But here is my husband's lesson: when we search for information, we don't all get the same results.

My husband, lying in bed next to me, Googled "current studies on vaccines and autism. " His results showed the most recent study from the '90s. Therefore, he thought investing in more recent research was reasonable.

Here is the thing: we have more recent research. His algorithms aren't the same as mine. Since I read research and literature for a living, my search results always direct me to scientific literature first. In contrast, his search directs him to opinion pieces that require quite a bit of scrolling to get to any scientific literature.

He pointed out that this is likely true for the average American, which is likely feeding this misinformation beast on vaccines and autism. This is also why it is vitally important for healthcare professionals and scientists to improve their science communication styles to help inform the public at large.

Though I preach the need to fact-check things before sharing on social media, I have been forced to accept that it isn't quite as simple as I believed it to be.

So, for those of you struggling to find current robust evidence, here is an extensive list of studies that have found no link between vaccines and autism here.

Still, it is reasonable to want to understand ASD better, so let's talk about it.

Increased Rates of ASD

Recently, in his address to Congress, President Trump gave what seemed like a startling statistic that 1 in 36 people are diagnosed with ASD. Though President Trump tends to exaggerate a lot, he was correct on this statistic.2

After that speech, my mother-in-law called, and we chatted. She asked me about this claim. Once I conceded that it was true, we discussed why this statistic has changed.

Better Access to Care

There is better access to care in the sense of telehealth options. Studies have shown that children living in affluent areas are 80% more likely to get an ASD diagnosis when compared to children living in rural areas. 3 However, this has recently changed thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic.4

The pandemic made healthcare providers and facilities quickly change to fit patients' needs better, including increasing telehealth options. Since then, telehealth options for ASD diagnosis have improved, allowing for better access to healthcare providers for children living in previously underserved areas.4

Improved Diagnostic Tools

Two very different tools have become more regularly utilized for ASD diagnosis. The first is the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), which was created in 1998.5 This screening uses direct observation and interaction by a mental health professional to facilitate diagnosis.6

The other tool is the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT). This 2-stage parent report screening is often done universally at child well-visits to identify signs of autism meant to improve early diagnosis rates, which helps with early interventions.7

Changing Definitions of Autism

One of the things my mother-in-law said to me in our phone conversation was that she never remembered anyone having autism when she was growing up. Now, we all must remember our memories are pretty fallible. However, in this case, she is 100% correct; she did not know anyone diagnosed with autism when she was growing up because autism wasn't a diagnosis until 1980.8

So, if you grew up during or prior to the '60s, '70s, and likely much of the '80s and you don't recall anyone being diagnosed with autism, it's because the diagnosis either did not exist or was just being established.

Nonetheless, there is evidence of children with ASD as far back as the 1700s when they were described as "feral children." 8 Notably, in 1943, Leo Kanner made a landmark observation in which he described 11 children as presenting with "inborn autistic disturbances of affective contact" 8

In the 80s, the diagnosis only provided for "infantile autism," which is vastly different than today's definition, which is why there were so few people diagnosed with autism during that time. The definition didn't change until 1987 when "pervasive developmental disorder" was added. Another update in 2013 consolidated various conditions into one diagnosis: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). This consolidation of conditions covered more of the population, leading to higher diagnosis rates, yet it does not reflect a higher prevalence of ASD.8

Also of note, in the '60s, '70s, and much of the '80s, children who likely had autism were sent to institutions. They did not attend regular schools and were rarely seen in public. Today that has changed.8,9

Also, many people think of autism as a disability that includes symptoms such as being non-verbal and unable to care for oneself. However, when the spectrum widened, it encompassed many brilliant people who have contributed significantly to society. Some notable people with diagnosed ASD or suspected ASD include Elon Musk, Albert Einstein, Daryl Hannah, Tim Burton, Mozart, and Beethoven, just to name a few.8,9

More Adults Diagnosis

Many adults who missed the opportunity for proper diagnosis as children, either due to the narrow definition or the lack of any diagnostic criteria for autism, are now seeking a diagnosis. There has been a significant increase in adults diagnosed in recent years. This, of course, will increase the total number of people living with ASD and change statistics.10

It is estimated that around 2.2% of people over 18 have ASD. The most significant increase in diagnosis rates is among individuals aged 26 to 34. The diagnosis rate in this age group has increased by 450% from 2011 to 2022. No, you did not misread that; it says four HUNDRED-FIFTY percent.11

Often, adults seek an ASD diagnosis after their child receives a diagnosis. These adults report relating to the same signs and/or challenges they see their children experiencing.

Belief Changes

There have been shifting beliefs regarding ASD. Previously, autism was believed to be strictly associated with intellectual challenges and disabilities. However, a better understanding of ASD has found this isn't true for many who are on the ASD spectrum. Many individuals with ASD are of exceptionally high intelligence. As mentioned above.3

From 2000 to 2016, there was a 500% increase in diagnosis of individuals with ASD without intellectual disabilities. Though it was previously believed that most children with ASD had some type of intellectual disability, more recent studies indicate the opposite is true: more children with ASD do NOT have intellectual disabilities.3

This trend is suggested to be due to better recognition of children with ASD with average or above-average intellectual abilities. Ultimately, around 2-in-3 children with ASD do NOT have intellectual disabilities.3

Science on ASD is Improving

The scientific community has made great strides in their understanding of ASD. A few key discoveries include

· The identification of multiple autism-associated genes, including PLEKHA8 and VPS54.12

· ASD recurrence is ~10 times higher in families with a history of ASD.13

· Females with ASD have a higher burden of rare genetic mutations.14,15

· Genes associated with depression in parents are linked to ASD.16

· Maternal immune infections are a risk factor for ASD.17

· Environmental factors play a more significant role in heritability in specific geographic locations, primarily Sweden and the UK.18

· Females carrying ASD genetic variations are resilient and often go undiagnosed.15

· Females are more likely to camouflage signs and symptoms by pretending to fit in.19

· ASD is associated with sleep disturbances in children, adolescents, and adults.20

· ASD may begin in utero. Prenatal ultrasound in the second trimester of pregnancy could identify early signs of ASD.21

If you still believe vaccines have a potential link to autism, take some time to read the studies in the link I provided on vaccines and autism. I encourage you to scrutinize them. Then, ask yourself if putting more money into this area of research is a better choice than moving forward with the research on autism and the genetic and other environmental links we have found.

We have been making some significant headway in this area of science; there is no need to pause or put it in reverse to invest in research that has been done ad nauseam.References

1. Bell, A. (2024, April 10). Is Autism Genetic? UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine. https://medschool.ucla.edu/news-article/is-autism-genetic#:~:text=QUICK%20FACTS:-,Is%20Autism%20Hereditary?,Geschwind.

2. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). (2024, May 16). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/autism/data-research/index.html

3. Shenouda J, Barrett E, Davidow AL, et al. Prevalence and Disparities in the Detection of Autism Without Intellectual Disability. Pediatrics. 2023;151(2):e2022056594. doi:10.1542/peds.2022-056594. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36700335/

4. Myrick, K.L., Mahar, M, and DeFrances, C.J. (2024, February). Telemedicine Use Among Physicians by Physician Specialty: United States, 2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db493.htm#:~:text=The%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic%20necessitated,%25%20(1%2C2).

5. Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):205-223. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11055457/

6. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule Assessment. (2024, November 27). National Health Service. https://bedslutonchildrenshealth.nhs.uk/neurodiversity-support/neurodevelopmental-assessment-and-diagnosis-process/autism-diagnostic-observation-schedule-ados-assessment/#:~:text=The%20autism%20diagnostic%20observation%20schedule,restricted%20behaviours

7. Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT). (2022, March 2). Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.research.chop.edu/car-autism-roadmap/modified-checklist-for-autism-in-toddlers-m-chat

8. Rosen NE, Lord C, Volkmar FR. The Diagnosis of Autism: From Kanner to DSM-III to DSM-5 and Beyond. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(12):4253-4270. doi:10.1007/s10803-021-04904-1. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8531066/#:~:text=Several%20important%20changes%20were%2C%20accordingly,the%20name%20for%20the%20condition.

9. 20 Famous People with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). (n.d.). Behavioral Innovations. https://behavioral-innovations.com/blog/20-famous-people-with-autism-spectrum-disorder-asd/

10. 10. Levine, H. (2024, December 3). Autism: The Challenges and Opportunities of an Adult Diagnosis. Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/autism-the-challenges-and-opportunities-of-an-adult-diagnosis

11. Grosvenor LP, Croen LA, Lynch FL, et al. Autism Diagnosis Among US Children and Adults, 2011-2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(10):e2442218. Published 2024 Oct 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.42218. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2825472?utm_term=103024&utm_campaign=ftm_links&utm_medium=referral&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-8dmppuICnKf_yIa_TBsNEo2SP4r2_oygi2RTvxdfBUF6gUBDvVaYaXoTdGxQlTu0YWkJjHxSI7r1u8XJOBj_GplHgolmVrzP-JOsa3jMMFKuDHa2U&_hsmi=331721335&utm_source=For_The_Media

12. Brandler WM, Antaki D, Gujral M, et al. Paternally inherited cis-regulatory structural variants are associated with autism. Science. 2018;360(6386):327-331. doi:10.1126/science.aan2261. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29674594/

13. Ozonoff S, Young GS, Bradshaw J, et al. Familial Recurrence of Autism: Updates From the Baby Siblings Research Consortium. Pediatrics. 2024;154(2):e2023065297. doi:10.1542/peds.2023-065297. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39011552/

14. Antaki D, Guevara J, Maihofer AX, et al. A phenotypic spectrum of autism is attributable to the combined effects of rare variants, polygenic risk and sex [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2022 Aug;54(8):1259. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01145-5.]. Nat Genet. 2022;54(9):1284-1292. doi:10.1038/s41588-022-01064-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41588-022-01064-5

15. Wigdor EM, Weiner DJ, Grove J, et al. The female protective effect against autism spectrum disorder. Cell Genom. 2022;2(6):100134. Published 2022 Jun 8. doi:10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100134. https://www.cell.com/cell-genomics/fulltext/S2666-979X(22)00063-5?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS2666979X22000635%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

16. Havdahl A, Wootton RE, Leppert B, et al. Associations Between Pregnancy-Related Predisposing Factors for Offspring Neurodevelopmental Conditions and Parental Genetic Liability to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Autism, and Schizophrenia: The Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(8):799-810. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1728. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9260642/

17. Nudel R, Thompson WK, Børglum AD, et al. Maternal pregnancy-related infections and autism spectrum disorder-the genetic perspective. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):334. Published 2022 Aug 16. doi:10.1038/s41398-022-02068-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-022-02068-9

18. Reed ZE, Larsson H, Haworth CMA, et al. Mapping the genetic and environmental aetiology of autistic traits in Sweden and the United Kingdom. JCPP Adv. 2021;1(3):e12039. doi:10.1002/jcv2.12039.https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9379966/

19. Ross A, Grove R, McAloon J. The relationship between camouflaging and mental health in autistic children and adolescents. Autism Res. 2023;16(1):190-199. doi:10.1002/aur.2859. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36416274/

20. Lampinen LA, Zheng S, Taylor JL, et al. Patterns of sleep disturbances and associations with depressive symptoms in autistic young adults. Autism Res. 2022;15(11):2126-2137. doi:10.1002/aur.2812. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36082844/

21. Regev O, Hadar A, Meiri G, et al. Association between ultrasonography foetal anomalies and autism spectrum disorder. Brain. 2022;145(12):4519-4530. doi:10.1093/brain/awac008.https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/145/12/4519/6509260?login=false